Just joking.

If you’re reading this post then you’ve probably flicked through a few of my others; if so you’ll know I consider myself in conflict with much of the twenty-first century; despite this I do embrace the majority of transformation occurring, including the technological. And you’ve also probably discovered that I live in two countries - not simultaneously of course! And these two realities have led me to the issue that I’m exploring here.

My mobility has forced me to embrace one distressing decision; I now almost never buy paper books anymore because their weight and volume are prohibitive. Why distress? Because I am someone who cherishes books and I’ve bought thousands which explains, in part, how I have managed to remain a pauper even while enjoying a handsome salary for years. Books have been an obsession throughout my life and even now, after taking extreme steps to de-clutter my life, I have hundreds in storage.

Winston Churchill explained how I feel about books so much better than could I: "If you cannot read them, any rate … fondle them. Peer into them … let them fall open where they will, … Set them back on the shelf with your own hands … If they cannot be your friends, let them at any rate be your acquaintances."

Alas now my books are but ephemeral wisps of digital data on by eReader, my tablet, and my phone; sadly there’s no fondling these ‘books’, and I’m not sure I can make, or want to make, the acquaintance of millions of bits and bytes - especially when they are arranged with so little attention to aesthetics. So in the search for mobility I have eschewed leather and other lustrous bindings, thick creamy deckle-edged paper, textures, the visual allure of fonts beyond Times and Arial postscript, and I’ve sold my soul to clinical technology in return for the promise of digital transcontinental transportability.

The other day I was thinking about what we consumers have come to accept as being perfectly acceptable treatment in this digital age.

Let’s imagine, for a moment, that as you approached the entrance to your favourite bookstore you were asked to produce some identification before being allowed inside; few of us, I suggest, would consider this acceptable treatment.

And yet that’s exactly what happened to me the other day when I was challenged for ID as I tried to access the Amazon Kindle store on my smartphone; I meekly waited until I returned home and browsed Amazon on my laptop without needing to login.

How compliant I’ve become; and how little about this experience seems to shock, or enrage. I suppose the rationale for providing an ID is security although if some other person shoulders their way into my Kindle store what are they going to do? Buy me some books? Doesn’t sound like much of a scam to me.

And our compliant state is even more surprising because access to the world’s knowledge is rapidly being monopolised by a diminishing number of companies. And I wonder if that isn’t a cause for concern because access to knowledge is fundamental to many of the freedoms that we enjoy.

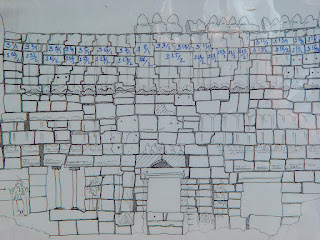

In around 50BC the great library at Alexandria, the greatest centralised knowledge repository of the known world, was razed to the ground and it plunged civilization back into an era in which written knowledge was scattered, scroll by scroll, from central Asia to the western gateway of the Mediterranean and exchanging knowledge happened at the speed of a cart, and even then, only to and from where cart tracks led.

This knowledge fragmentation had considerable impact because the educated, and their masters, were the sole custodians of, and gatekeepers to, knowledge and this created a world in which few knew what knowledge was available, the benefits to be gained from accessing it, or where it resided; across Europe the dark ages was probably extended hundreds of years by this barrier to accessing knowledge.

So knowledge dispersal worked against human advancement by promoting ignorance and perverting thought.

Then the advent of movable type and the printing press opened the floodgates and knowledge flooded the world; knowledgeflood 1.0 is perhaps how we would describe it today.

Now the Internet and search engines have enabled knowledgeflood 2.0, and we have the best of both worlds: decentralised and disseminated knowledge which is simultaneously centralised through the wizardry of the Internet; my browser converts my laptop to the world’s largest library and archive.

For me the convenience of digital books is fantastic and I have hundreds of books stored on my tablet, a device the size of a small paperback - and I also have hundreds in storage that take up the space of a two car garage; so I’ve made progress - at least in the volumetric sense. And in my life, one is carry on baggage, and the other would max-out my Visa card at check-in.

So what’s to worry about? Well - it’s not the convenience of knowledge digitisation, or the increase in the types of media upon which knowledge can now be stored and distributed, and it’s not even the capability to share using the Internet; rather it’s that once upon a time when I bought a book - I owned that book - and I could have that book in my possession. But now ownership and access is far less certain with digital knowledge.

In ‘The Googlization of Everything’ Siva Vaidhyanathan writes, ‘... there has never been a company with explicit ambitions to connect individual minds with information on a global - in fact universal - scale. The scope of Google's mission sets it apart from any company that has ever existed in any medium.

He also writes ‘ … no single state, firm or institution in the world has as much power over Web-based activity as Google does.’

And, ‘Google is the dominant way we navigate the Internet, and thus the primary lens through which we experience both the local and the global, and it has remarkable power to set agendas and alter perceptions. Its biases (valuing popularity over accuracy, established sites over new, and rough rankings over more fluid and multidimensional models of presentation) are built into its algorithms. And those biases affect how we value things, and navigate the worlds of culture and ideas. In other words we are folding the interface and structures of Google into our very perceptions’.

I wonder, is civilisation up for sale?

And how easily could access convenience be replaced by inconvenience? Perhaps digitisation is a two edged sword?

Imagine, for example, we awakened one morning and collectively tried to log on to Google only to discover that access was denied because Google had been acquired by an totalitarian regime, or access suddenly depended on a hefty fee, or that our digital book provider had gone broke, and our books were no longer available to us.

Now it would be possible to see this post as anti-Internet or anti-Google - but quite the reverse - the services that Google provide or enable are now central to my life - and that again is the point.

The other day as I explored blogging I thought I would discover what the Google AdSense service offered and to astonishment I was confronted with a message telling me that my AdSense account had been frozen due to inappropriate activity that breached my agreement with Google; this news was delivered with the reassuring words that if I wanted to complete a comprehensive questionnaire then Google may reconsider my case.

As an aging warrior I am often begrudging in my adherence to stupid laws and moronic guidelines - but even so I don’t break the law, especially when my opponent would be global giant Google so I’ve certainly done nothing to earn this rebuke - and I can be sure of this because I’ve never attempted to access the AdSense service; I’m absolutely sure of my innocence!

Now I’m not sure if you have you ever tried to speak to anyone at Google? Forget it, they’ve never heard of the device that most of us use to communicate when it really matters - the telephone.

So I eventually sent Google this message: ‘I am astonished. To the best of my knowledge I have never given Google any occasion to treat me in any way than a valued user. I have to say that the complete inability to engage with someone also astonishes me. It is somewhat reminiscent of a 'star chamber' where I stand accused of some unknown act and I have been offered no explanation, no charges have been laid, I have no assistance in preparing or delivering my defense, and I have no way of assessing the likelihood of reprieve. Dreadful.’

Google had warned me that any plea might fall on deaf ears, that any complaint against me might be upheld and I would remain a cyber black sheep, or that I may get an answer in three or four weeks - they acknowledged they don’t have many resources dedicated to reviewing these cases of infringement. I never received a reply.

Perhaps after all this you’re thinking so what? Good question and I’m not sure I have a complete answer. In short I’m pleased that so much information is accessible. But I do wonder what would happen if our access to the knowledge base were restricted - and of course, it’s not just knowledge because Google, and the Internet, are now such an essential part of my life; I am now, as it were, ‘in the cloud’.

Now Google is the custodian of this blog draft, and the blog itself, twenty-five thousand of my photographs are out there, together with more and more of my documents spinning through cyberspace, my diary, your twitter address, and my to-do lists, the pages of my digital notebooks, and my banking details, my health records, tax records, my accounts and … what else is there?

Gulp. I hope no one pulls the plug without warning! Because if they do, the cyber-me will disappear. And I’ll be left without my ID!

Sunday, 17 July 2011

Saturday, 25 June 2011

So imagine, night has fallen, and beyond the outer temple enclosure in the jungle there is rustling, shrill cries, and throaty rumbling.

I’m not sure about other aging warriors, but I often wonder whether my later life decisions are sane and practical; is it practical, for example for me to move to Thailand?.

And then I get to thinking about life in the western world and the cultural differences with Asia and I perk up because I realise that staying put in Australia, for me, is not an option; and anyway discovering Asia has been a joy, and I’m always excited at the chance to return there.

One rewarding discovery for me has been the ancient Khmer empire; I recall during my mid to late twenties reading about Pol Pot and Cambodia and I remember never being quite clear about the complex drama that was being played out; I don’t know that I ever resolved the conundrum.

Flash forward to 2004 when I first visted Cambodia as a consequence of discovering a wonderful book, ‘Ruins of Angkor’, full of photographs taken in 1909 by Frenchman P. Dieulefils when the temples were probably little different from when Europeans first re-encountered them in mid nineteenth century; they were tumbling down, they were overgrown by grasses, shrubs and stained by mould, bat droppings, and by the accumulated filth of centuries. And yet, this in no way seemed to diminish the attraction of these extraordinary works of art – these great places of worship. In fact, their ruinous condition was their attraction.

Way back in a February post entitled Dames, Broads and Dolls, I wrote about apsara, celestial dancers, that adorn numerous khmer temples … and I’ve pondered on their similarity because no matter where you come across apsaras, there’s something about them – I’ve gazed at thousands. I’ve closely scrutinised hundreds of faces. There’s definitely something about them.

Georges Coedes, doyen of Khmer Empire academics until his death in 1969 wrote, ‘ … the figures of apsaras which adorn the walls of Angkor Wat are not there solely for the pleasure of the eye: their role is to transform this cold stone dwelling-place into a celestial palace’. So, it seems, he believed that these decorative girls – and all the other temple decorations - were more than simple representations of divine beings; rather he believed they were to evoke divine worlds and bring them to life - in the temple.

So imagine, night has fallen and beyond the outer temple enclosure in the jungle there is rustling, shrill cries, and throaty rumbling. Inside the temple, the great Khmer king Jayarvarman VII is making his way to the inner sanctum of Angkor Wat – his vast retinue of attendants follow although only he and the attending Brahman priests will climb to the highest terrace. The sound of the pacing thousands echo through the galleries and terraces.

Flares flicker and gutter as breezes find their way along colonnades and through windows and doors, golden thread woven into vividly coloured banners shimmer, fabric ripples, incense drifts – and across the rough hewn stone walls shadows tumble, chase and slide at the passing of this vast crowd.

Now the celestial dancers are not so inert – but rather they seem to seductively undulate, sway, and deeply genuflect - and the guardian devatas in deepening shadows alternately recede and emerge as flames flicker. Light gleams on vast golden Buddhas and Hindu deities. Bats zigzag and squeak. Bells and gongs ring, and other instruments tinkle. And fruit and blossom offerings scent the humid night.

The king strides the great encircling galleries with their carved reliefs - floating apsaras in heaven and tormented souls in hell – torture and mayhem – and scenes of the royal court - he pauses by an image his grand-father King Suryavarman II who commissioned this vast building, standing on his war elephant leading a vast army of Khmer and Siamese troops on its way to wage war – to kill and plunder, pillage and enslave.

If apsaras talked - and who knows maybe they do when the tourist hoards are gone - they would tell you they are accustomed to molestation and violence. They have been fondled by perhaps millions of visitors over hundreds of years, for centuries robbers have been hacking their inscrutable faces from shapely bodies to make a quick buck, and restoration works have deconstructed, chemically treated and reconstructed thousands.

The most recent apsara pogrom occurred in temples where Pol Pot’s armed thugs took refuge between 1975 and 1979 amusing themselves using life-sized apsaras for target practice. Happily, by and large, they otherwise left the temples relatively unharmed – a miracle given what the Khmer Rouge did to fellow citizens – these acts of temple vandalism were the very least of their mindless activities.

If you visit Ta Prohm at Tonli Bati, a tiny Khmer temple 20 or so kilometres from Phnom Penh, the smiling apsaras you see are in stark contrast to the depressing depressions of the killing fields of Choeung Ek a few kilometres away where about 17,000 were slaughtered after being brutally tortured by interrogators - fellow citizens - at prison S-21. At the tall glass-sided memorial there are no smiles – just the bared upper molars of more than 8,000 cavernous skulls arranged on shelves as if in some library in the bowels of hell. Oh that these poor souls could be renovated as effectively as apsaras.

Fortunately, in the early nineteen-eighties the Archaeological Survey of India – the ASI - was selected to undertake Angkor restoration works; their proposals were accepted because of their sympathy with Khmer culture and similar work done on many Indian temples.

The scale of the renovation works was staggering – entire portions of the temple were rebuilt – or at least renovated. Bat nesting was eliminated and the stone-corroding acid from their droppings was neutralised. Micro-vegetation was stripped away. Damaged stones were rejuvenated. Surfaces were chemically cleaned, and protected. And inevitably, fortunately, the apsaras received the same TLC – which is why their smiles are broader than any other Angkor apsaras. Yes, you’re right – that’s not true – but it would be nice to think it was, given the difficulty involved in the restoration.

Like the ugly duckling that became a swan - Angkor Wat was transformed; and all this was achieved as a, post Pol Pot regime, civil war raged around Angkor. India’s Ambassador to Cambodia later wrote: ‘There was no electricity, no health facilities, no communication with the outside world. In short, the working conditions were extreme. But for seven to eight months at a stretch for seven consecutive years from December 1986, the ASI experts spent all their energies in saving Angkor Wat, shoulder to shoulder with their Khmer brethren’.

The work of preserving Angkor Wat – and many other temples – continues with the expertise of many nations.

However, not all the numerous temples in the Angkor region received the same focused attention as Angkor Wat. Even today, in temples where carvings are more exposed to weather, stone contours have softened and only the faintest images remain, moss coats surfaces, tiny plants thrive between blocks, and the webs of marauding spiders form gossamer veils. And in some temples it’s clear that restoration has been, at best, less than perfect – especially when Frangipani’s upper torso has lily’s navel - because sometimes reconstructions are completed with stone blocks that are available - rather than those that are missing.

If you wander through the valleys, across the plains and over hillsides of the one-time Khmer Empire you'll get to meet many more of these apsara beauties, some as fresh and clean as if they were carved yesterday and others not. Their costumes and appearance change depending on the era in which the carvers gave birth to their creations. And there is something about them – some shared characteristic.

Apsara frequently hold flowers, or their diaphanous sarongs are discretely decorated with blossoms, and sometimes they are surrounded by elaborate carved foliage, or the background from which they protrude is a field of repetitive floral symbols.

Perhaps the most common flower represented is the sacred flower of Hindu mythology, the lotus and many apsaras hold a long stem lotus that loops behind their neck.

Every apsara is unique – some barely so - but others are like chalk and cheese. They all have as much variation in eyebrows, eyes, chins, lips and mouths, gestures, body shape, hairstyle, and apparel and accessories as you’d see as any crowded mall anywhere in the world.

I am told several hold books – and that only two, among all the smiles, display teeth - I can vouch that there is one. But I won’t tell you where she is – go look for yourself.

But what is it about them? There is a consistent feature. It’s on the tip of my tongue.

In my first post about apsaras I began by writing that many Asian women have extraordinarily exotic features – added to which they frequently wear clothing that tantalises – like the Chinese cheongsam and the Vietnamese ao dais, for example.

If you hang around you’ll be able to revisit the Khmer Empire, apsaras and the similarity they universally share, and beautiful women in another post some time soon.

Thanks for spending these few minutes with me.

And then I get to thinking about life in the western world and the cultural differences with Asia and I perk up because I realise that staying put in Australia, for me, is not an option; and anyway discovering Asia has been a joy, and I’m always excited at the chance to return there.

One rewarding discovery for me has been the ancient Khmer empire; I recall during my mid to late twenties reading about Pol Pot and Cambodia and I remember never being quite clear about the complex drama that was being played out; I don’t know that I ever resolved the conundrum.

Flash forward to 2004 when I first visted Cambodia as a consequence of discovering a wonderful book, ‘Ruins of Angkor’, full of photographs taken in 1909 by Frenchman P. Dieulefils when the temples were probably little different from when Europeans first re-encountered them in mid nineteenth century; they were tumbling down, they were overgrown by grasses, shrubs and stained by mould, bat droppings, and by the accumulated filth of centuries. And yet, this in no way seemed to diminish the attraction of these extraordinary works of art – these great places of worship. In fact, their ruinous condition was their attraction.

Way back in a February post entitled Dames, Broads and Dolls, I wrote about apsara, celestial dancers, that adorn numerous khmer temples … and I’ve pondered on their similarity because no matter where you come across apsaras, there’s something about them – I’ve gazed at thousands. I’ve closely scrutinised hundreds of faces. There’s definitely something about them.

Georges Coedes, doyen of Khmer Empire academics until his death in 1969 wrote, ‘ … the figures of apsaras which adorn the walls of Angkor Wat are not there solely for the pleasure of the eye: their role is to transform this cold stone dwelling-place into a celestial palace’. So, it seems, he believed that these decorative girls – and all the other temple decorations - were more than simple representations of divine beings; rather he believed they were to evoke divine worlds and bring them to life - in the temple.

So imagine, night has fallen and beyond the outer temple enclosure in the jungle there is rustling, shrill cries, and throaty rumbling. Inside the temple, the great Khmer king Jayarvarman VII is making his way to the inner sanctum of Angkor Wat – his vast retinue of attendants follow although only he and the attending Brahman priests will climb to the highest terrace. The sound of the pacing thousands echo through the galleries and terraces.

Flares flicker and gutter as breezes find their way along colonnades and through windows and doors, golden thread woven into vividly coloured banners shimmer, fabric ripples, incense drifts – and across the rough hewn stone walls shadows tumble, chase and slide at the passing of this vast crowd.

Now the celestial dancers are not so inert – but rather they seem to seductively undulate, sway, and deeply genuflect - and the guardian devatas in deepening shadows alternately recede and emerge as flames flicker. Light gleams on vast golden Buddhas and Hindu deities. Bats zigzag and squeak. Bells and gongs ring, and other instruments tinkle. And fruit and blossom offerings scent the humid night.

The king strides the great encircling galleries with their carved reliefs - floating apsaras in heaven and tormented souls in hell – torture and mayhem – and scenes of the royal court - he pauses by an image his grand-father King Suryavarman II who commissioned this vast building, standing on his war elephant leading a vast army of Khmer and Siamese troops on its way to wage war – to kill and plunder, pillage and enslave.

If apsaras talked - and who knows maybe they do when the tourist hoards are gone - they would tell you they are accustomed to molestation and violence. They have been fondled by perhaps millions of visitors over hundreds of years, for centuries robbers have been hacking their inscrutable faces from shapely bodies to make a quick buck, and restoration works have deconstructed, chemically treated and reconstructed thousands.

The most recent apsara pogrom occurred in temples where Pol Pot’s armed thugs took refuge between 1975 and 1979 amusing themselves using life-sized apsaras for target practice. Happily, by and large, they otherwise left the temples relatively unharmed – a miracle given what the Khmer Rouge did to fellow citizens – these acts of temple vandalism were the very least of their mindless activities.

If you visit Ta Prohm at Tonli Bati, a tiny Khmer temple 20 or so kilometres from Phnom Penh, the smiling apsaras you see are in stark contrast to the depressing depressions of the killing fields of Choeung Ek a few kilometres away where about 17,000 were slaughtered after being brutally tortured by interrogators - fellow citizens - at prison S-21. At the tall glass-sided memorial there are no smiles – just the bared upper molars of more than 8,000 cavernous skulls arranged on shelves as if in some library in the bowels of hell. Oh that these poor souls could be renovated as effectively as apsaras.

Fortunately, in the early nineteen-eighties the Archaeological Survey of India – the ASI - was selected to undertake Angkor restoration works; their proposals were accepted because of their sympathy with Khmer culture and similar work done on many Indian temples.

The scale of the renovation works was staggering – entire portions of the temple were rebuilt – or at least renovated. Bat nesting was eliminated and the stone-corroding acid from their droppings was neutralised. Micro-vegetation was stripped away. Damaged stones were rejuvenated. Surfaces were chemically cleaned, and protected. And inevitably, fortunately, the apsaras received the same TLC – which is why their smiles are broader than any other Angkor apsaras. Yes, you’re right – that’s not true – but it would be nice to think it was, given the difficulty involved in the restoration.

Like the ugly duckling that became a swan - Angkor Wat was transformed; and all this was achieved as a, post Pol Pot regime, civil war raged around Angkor. India’s Ambassador to Cambodia later wrote: ‘There was no electricity, no health facilities, no communication with the outside world. In short, the working conditions were extreme. But for seven to eight months at a stretch for seven consecutive years from December 1986, the ASI experts spent all their energies in saving Angkor Wat, shoulder to shoulder with their Khmer brethren’.

The work of preserving Angkor Wat – and many other temples – continues with the expertise of many nations.

However, not all the numerous temples in the Angkor region received the same focused attention as Angkor Wat. Even today, in temples where carvings are more exposed to weather, stone contours have softened and only the faintest images remain, moss coats surfaces, tiny plants thrive between blocks, and the webs of marauding spiders form gossamer veils. And in some temples it’s clear that restoration has been, at best, less than perfect – especially when Frangipani’s upper torso has lily’s navel - because sometimes reconstructions are completed with stone blocks that are available - rather than those that are missing.

If you wander through the valleys, across the plains and over hillsides of the one-time Khmer Empire you'll get to meet many more of these apsara beauties, some as fresh and clean as if they were carved yesterday and others not. Their costumes and appearance change depending on the era in which the carvers gave birth to their creations. And there is something about them – some shared characteristic.

Apsara frequently hold flowers, or their diaphanous sarongs are discretely decorated with blossoms, and sometimes they are surrounded by elaborate carved foliage, or the background from which they protrude is a field of repetitive floral symbols.

Perhaps the most common flower represented is the sacred flower of Hindu mythology, the lotus and many apsaras hold a long stem lotus that loops behind their neck.

Every apsara is unique – some barely so - but others are like chalk and cheese. They all have as much variation in eyebrows, eyes, chins, lips and mouths, gestures, body shape, hairstyle, and apparel and accessories as you’d see as any crowded mall anywhere in the world.

I am told several hold books – and that only two, among all the smiles, display teeth - I can vouch that there is one. But I won’t tell you where she is – go look for yourself.

But what is it about them? There is a consistent feature. It’s on the tip of my tongue.

In my first post about apsaras I began by writing that many Asian women have extraordinarily exotic features – added to which they frequently wear clothing that tantalises – like the Chinese cheongsam and the Vietnamese ao dais, for example.

If you hang around you’ll be able to revisit the Khmer Empire, apsaras and the similarity they universally share, and beautiful women in another post some time soon.

Thanks for spending these few minutes with me.

Saturday, 18 June 2011

Maturity is no antidote against stupidity!

So this morning as I clamber from my bed I know with a certainty that I consumed too much alcohol last night. Way too much. Stupid. Absurd.

So in my fragile state I’m tapping away at this post because I’ve missed blogging in recent months, and because my own stupidity reminds me that I have thoughts I’d like to share about this very subject.

Stupidity. I’m not sure about your world, but mine really is full of breathtaking stupidity.

More and more I see ordinary citizens of the world in which I live being treated like helpless children despite their obvious maturity; or like criminals instead of hapless innocents trapped in a mire of revenue-raising regulations; or heroes when they should be perceived as villains; or wealthy when in fact they are just making ends meet as taxes and the cost of living soar; or intellectuals when they are nothing more than pompous and misguided blowhards. I won’t go on, at 68 time is too short.

In previous posts I’ve identified my ‘PC21’ - my personal conflicts with the twenty-first century - and this list perfectly illustrates some of the conflicts that often cause me to feel disenfranchised, as stupidity gets a tighter and tighter grasp on society, and as it slowly strangles my own ability to live my very modest and unobtrusive lifestyle.

Since I last posted I’ve spent some time in my Thai home; living in a third world country is a welcome reprieve from western society.

But I've also spent some time in corporate Australia and there’s certainly no escape from stupidity there. Less people doing more and more work, multitasking our way to mediocrity while all the time loudly proclaiming corporate values of quality and thought leadership; eliminating competent employees and then immediately replacing them with more educated but less competent and capable people - qualifications are rarely a substitute for experience; demands for increased productivity and quality while acting in ways that reduce worker engagement; shunting people around organisational structures that on paper work perfectly, but in the real world defy implementation; English-mangling jargon that makes the simple incomprehensible; it’s a place where talking in meetings eliminates any possibility to doing; and, in my own area of specialisation, we’re trying to turn selling into a science rather than mastering the art.

This is unquestioningly the age of absurdity. But there’s not much point whining - better to fight back. But what to do? What weapons do I have against this global tsunami of absurdity? Or do I have a shield large enough to protect me?

Well, I’ve already posted the steps that I’ve taken to try and counter my personal conflicts with this century.

And recently I’ve been trying to make sense of this age, and trying to discover whether others have similar frustrations to my own, so I’ve been reading ‘The age of absurdity’; for me it’s riveting and if you find yourself wondering what has happened to life as you once knew it, then this is a book for you.

It’s one of the few paperbacks I have, given the transient nature of my lifestyle, and its pages are scored with underlined paragraphs and graffiti, pages are dogeared, it falls open at many places where the spine has been creased, and it has post-it notes and scraps of paper poking out between every other page.

If you sense that you are in conflict with the twenty-first century I highly recommend you read ‘The age of absurdity’ and react, and resist some of the nonsense that threatens to overwhelm us.

Reading it has certainly helped me see the absurdity - the stupidity - that pervades our society and it’s given me great new insights that help me stiffen my resolve to resist.

How to resist? What to do? It’s tough because the absurdity of this age is omnipresent. But on a practical level here’s my discipline:

By applying these disciplines I don’t eliminate absurdity, but I do cause my focus to be on what I am doing, rather than what everyone else is doing; and that works for me.

As is self evident, Buddha accompanies me on this journey of reflection and in an early post I wrote that it was ‘my growing conviction is that there could be no better guide, no better plan, for responding to pc21, than the way for living life as proposed by the Buddha’; his eightfold path is a very accessible tool for living.

Author Michael Foley writes in the ‘The age of absurdity’ opening chapter, that ‘Buddha’s metaphor for the liberated mind was a sword drawn from its scabbard’ - so perhaps Buddha’s image and my self-professed role as an aging warrior are entirely appropriate for trying to liberate myself from this age of absurdity?

And perhaps maturity can be an antidote to absurdity - and stupidity?

http://www.amazon.com/Age-Absurdity-Modern-Makes-Happy/dp/1847396275/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1308383280&sr=1-1

So in my fragile state I’m tapping away at this post because I’ve missed blogging in recent months, and because my own stupidity reminds me that I have thoughts I’d like to share about this very subject.

Stupidity. I’m not sure about your world, but mine really is full of breathtaking stupidity.

More and more I see ordinary citizens of the world in which I live being treated like helpless children despite their obvious maturity; or like criminals instead of hapless innocents trapped in a mire of revenue-raising regulations; or heroes when they should be perceived as villains; or wealthy when in fact they are just making ends meet as taxes and the cost of living soar; or intellectuals when they are nothing more than pompous and misguided blowhards. I won’t go on, at 68 time is too short.

In previous posts I’ve identified my ‘PC21’ - my personal conflicts with the twenty-first century - and this list perfectly illustrates some of the conflicts that often cause me to feel disenfranchised, as stupidity gets a tighter and tighter grasp on society, and as it slowly strangles my own ability to live my very modest and unobtrusive lifestyle.

Since I last posted I’ve spent some time in my Thai home; living in a third world country is a welcome reprieve from western society.

But I've also spent some time in corporate Australia and there’s certainly no escape from stupidity there. Less people doing more and more work, multitasking our way to mediocrity while all the time loudly proclaiming corporate values of quality and thought leadership; eliminating competent employees and then immediately replacing them with more educated but less competent and capable people - qualifications are rarely a substitute for experience; demands for increased productivity and quality while acting in ways that reduce worker engagement; shunting people around organisational structures that on paper work perfectly, but in the real world defy implementation; English-mangling jargon that makes the simple incomprehensible; it’s a place where talking in meetings eliminates any possibility to doing; and, in my own area of specialisation, we’re trying to turn selling into a science rather than mastering the art.

This is unquestioningly the age of absurdity. But there’s not much point whining - better to fight back. But what to do? What weapons do I have against this global tsunami of absurdity? Or do I have a shield large enough to protect me?

Well, I’ve already posted the steps that I’ve taken to try and counter my personal conflicts with this century.

And recently I’ve been trying to make sense of this age, and trying to discover whether others have similar frustrations to my own, so I’ve been reading ‘The age of absurdity’; for me it’s riveting and if you find yourself wondering what has happened to life as you once knew it, then this is a book for you.

It’s one of the few paperbacks I have, given the transient nature of my lifestyle, and its pages are scored with underlined paragraphs and graffiti, pages are dogeared, it falls open at many places where the spine has been creased, and it has post-it notes and scraps of paper poking out between every other page.

If you sense that you are in conflict with the twenty-first century I highly recommend you read ‘The age of absurdity’ and react, and resist some of the nonsense that threatens to overwhelm us.

Reading it has certainly helped me see the absurdity - the stupidity - that pervades our society and it’s given me great new insights that help me stiffen my resolve to resist.

How to resist? What to do? It’s tough because the absurdity of this age is omnipresent. But on a practical level here’s my discipline:

- I try to simplify my thinking - and eliminate or reduce the mental muddle that often accompanies anything we do in this age, and

- I try to focus on doing everything with complete attention rather than multitasking myself into mediocrity, and

- I try to eliminate or avoid sources of information, like newspapers, that cause me to confront the absurdity, and

- I try to avoid accumulating.

By applying these disciplines I don’t eliminate absurdity, but I do cause my focus to be on what I am doing, rather than what everyone else is doing; and that works for me.

As is self evident, Buddha accompanies me on this journey of reflection and in an early post I wrote that it was ‘my growing conviction is that there could be no better guide, no better plan, for responding to pc21, than the way for living life as proposed by the Buddha’; his eightfold path is a very accessible tool for living.

Author Michael Foley writes in the ‘The age of absurdity’ opening chapter, that ‘Buddha’s metaphor for the liberated mind was a sword drawn from its scabbard’ - so perhaps Buddha’s image and my self-professed role as an aging warrior are entirely appropriate for trying to liberate myself from this age of absurdity?

And perhaps maturity can be an antidote to absurdity - and stupidity?

http://www.amazon.com/Age-Absurdity-Modern-Makes-Happy/dp/1847396275/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1308383280&sr=1-1

Wednesday, 23 February 2011

Wanted. Superheroes.

Just recently I’ve been reading ‘Watchmen’, an Alan Moore graphic novel first published in twelve installments during 1986 and 1987; many graphic novel aficionados claim it is the finest example of this publishing genre.

The story centres on a group of superheroes in the style of Superman and Spiderman, by which I mean they are costumed; except the ‘Watchmen’ superheroes are really just ordinary citizens, vigilantes, poncing around in spandex. The one exception is Doctor Manhattan – he’s genuinely a superhero but he spends a great deal of time naked, which maybe explains why he’s blue; but then again, maybe not.

You might be forgiven for thinking that an aging warrior should be reading a more traditional story form, just words on a page, and typically I do, but I came across this graphic novel while reading a traditional book; and I was intrigued.

I have been reading ‘Jonathon Strange and Mr Norrell’, a captivating Susanna Clarke novel about magic in nineteenth-century England, so I checked out her web site and discovered she lists the ‘Watchman’ as one of the most influential books she’s ever read. I was even more intrigued.

So I had to discover the ‘Watchmen’ for myself; discovering is, I believe, one of the marks of an aging warrior.

Anyway, the story has me thinking about the idea of watchmen – super heroes by definition, if not if fact, who are engaged in watching; but what and who should they be watching?

Well, I can only speak for the country in which I live half my life – Australia; here it’s very clear that we need watchmen, and it’s also clear whom they should be watching: our politicians and bureaucrats.

In Australia our current federal government is spending our hard-earned tax dollars - some would say squandering - at a rate never before experienced in Australia.

Yet despite this, the programs launched since their ascendancy to power have been characterised by failure: school buildings constructed by companies that enjoy union or government patronage that cost more than twice comparable buildings built by companies without similar patronage; borders that are leaking like a sieve; debate in our parliament has been reduced to the standards of a vaudeville act – a bad one at that; legislation now cripples every activity – from the most mundane to the crucial; cleanup activities after major flooding and several cyclones are limping along and ordinary people sit waiting and wondering as our army of bureaucratic incompetents design forms and sip cafe latte; common sense infrastructure initiatives such as dams, which could have helped contain the waters that now flood vast stretches of the eastern half of our continent, have been dumped in favour of expensive energy-guzzling desalination plants which are no longer needed for the foreseeable future; and tax cripples business, particularly small business, which is the heartbeat of our nation’s commerce.

Yes. We need as many superheroes as we can find to watch this mess and alert the endangered citizens of Australia.

So where do we find them? Where are these superheroes?

Well. It’s you and me. Come on aging warriors: this is a battle cry.

But please don’t ask me to wear a spandex costume!

Wednesday, 16 February 2011

Outlaw or hero?

So, in my last post I listed what I’ve been doing as an aging warrior to counter my PC21 – my personal conflicts with the twenty-first century.

What I didn’t explain is what these conflicts are, or perhaps more accurately, what the conflicts are primarily caused by.

Here’s the headlines:

- Corporate greed, hypocrisy, and incompetence.

- Lack of integrity within, and unchecked profligacy and abuses of process and power by, government and bureaucracy.

- Lack of integrity within, and unchecked profligacy and abuses of process and power by, government and bureaucracy.

- News media bias and manipulation.

- Expectations of the society in which I live.

- Expectations of the society in which I live.

These causes are like four hydraulic rams pressing in from four directions and they edge ever forward into the shrinking central space where I stand, ineffectively pushing first against one - and then another.

But I have no control or influence over these rams – so, I will either be crushed or I must remove myself from the shrinking central space; and thus from the conflict they represent.

Ekhart Tolle, modern day philosopher and teacher, offers three options for dealing with the places where we end up in life: change them, accept them, or leave them

And in a sense, after a great deal of consideration, I’ve adopted his advice – I’ve considered the shrinking space that the advancing rams have formed – and I’ve taken my leave.

I could put up with the place in which I’ve found myself, but that's the compromise I mentioned in my last post, and why should I compromise my life?

Ten years ago I stumbled across a profound remark made by Sigmund Freud that describes my whole life up until that point, and it has certainly shaped my life since: ‘Since the beginning of civilization, man has had but one choice, to conform or not to conform. If he conforms, he is a dead man. His life is over, his life's decisions predetermined by the society he joins with. If he chooses not to conform, he buys himself one more choice, to become outlaw or hero.’

I'm an aging warrior. But am I an outlaw, or hero? That’s for others to judge. Maybe you have an opinion?

Tuesday, 15 February 2011

Why am I musing, pondering and meditating?

This blog began with the idea that I would muse on the decisions I’ve made to create a life for myself in this latest – perhaps last chapter of my life; I’ve made these decisions as a mature adult that’s enjoyed a modestly colourful life.

The spark that ignited this self-examination was when I reached the tipping point at which I could no longer contaminate the potential of my ‘golden’ years by continuing to compromise as I struggle to live what life in Australia has become; or rather what life has been turned into.

The causes of my need to compromise are my personal conflicts with the twenty-first century: my PC21. I’ll get to these in another post.

In compromising my life I became angry; I am angry. Which is why I see myself as an aging warrior; I am shielding myself. And I am fighting back.

Why muse, ponder and meditate? Because I’d like to live my life in a way that fulfils my reasonable and very modest expectations and I’d like to manage the factors that can influence my life. The Swiss philosopher Henri Amiel wrote, 'To know how to grow old is the master-work of wisdom, and one of the most difficult chapters in the great set of living'.

I’d like to get these decisions right. I’d like to explore and investigate. And I’d like to think there may be other aging warriors that could benefit from my experiences.

So what steps have I taken to combat my PC21?

I have:

- eliminated debt.

- planned for an off-shore later life.

- simplified my life.

- done, and do, everything possible to remain gainfully employed.

- invested in daily self-improvement.

- tended towards a life of moderation, but not mediocrity.

- eliminated debt.

- planned for an off-shore later life.

- simplified my life.

- done, and do, everything possible to remain gainfully employed.

- invested in daily self-improvement.

- tended towards a life of moderation, but not mediocrity.

Every post I have made, and will make, here tells the story of my progress in this very personal endeavour.

Thanks for taking time to read my thoughts. And your thoughts would be very welcome.

Tuesday, 1 February 2011

Dames, Broads and Dolls.

It’s self-evident, even to an aging warrior, that many Asian women have extraordinarily exotic features – added to which they frequently wear clothing that tantalises – like the Chinese cheongsam and the Vietnamese ao dais, for example.

This being so, one is accustomed to coming across beautiful, seductive Asian women that turn heads – so, as I came across four gorgeous young women in the jasmine-scented Cambodian dusk, I was hardly surprised.

Four young ladies, clearly on their way to an exotic dance club or avant-garde, trendy bar; they were wearing diaphanous hip-hugging sarongs, broad belts that hung from shapely hips, ropes of pearls, pendants, bracelets and forearm cuffs, anklets and other exotic adornment - bling I suppose, would be the modern idiom – capped by extraordinary headwear and hairstyles interwoven with blossoms, tiaras and other striking ornamentation; this was coiffure that would have caused comment even at the Melbourne Cup, an Australian horse race noted for its trackside tonsorial, millinery and fashion excesses; it's an event at which aging warriors frequently make fools of themselves!

I recall these four girls as stupendously feminine - hippy – seductive – real knockouts; author Raymond Chandler would have called them dames, Sinatra – broads, and Bogart – dolls.

The Oxford Dictionary has numerous more quirky expressions to describe good-looking women including arm candy, boy toy, cupcake, glamour puss, nymphet, odalisque and perhaps my favourite, Mata Hari, the stage name of a Dutch, part-time oriental dancer and courtesan during the troubled times of World War I – her other career was spying, for which she was shot!

I’ll admit, the girls being bare-breasted took me somewhat aback – but this would not have been extraordinary when these dolly birds were carved in relief on the walls of Angkor Wat during the reign of Khmer King Suryavarman II, some time in the mid twelfth century. Women have gone bare-breasted in Cambodia for hundreds of years.

These four foxy ladies are apsaras – and there are similar sisters called devatas; in scholarly explanations there are differences between the two, but the descriptions often seem interchangeable and inconsistent.

In short apsaras are female divinities or celestial dancers, so it is hardly surprising that in many carved reliefs they are shown in flight – perhaps in the dead of night, they still make an occasional circuit around their temple? Apsaras also come in many shapes and sizes ranging from life-sized to dinner plate-size. Some are carved in high relief, standing well clear of their background – and some are low relief, so shallowly carved they seem barely to cling to their allotted stone - it’s as if a strong breeze would wipe their existence clear away.

Myth has it that apsaras were born when the Indian deity Vishnu churned the ocean of milk to produce the elixir of life; this tale is told at great length, in 50 metres of stupendous reliefs in the eastern gallery of Angkor Wat. Generally the tale incorporates a pot of gold – a vial of the elixir of life somewhere in view but, in this Angkor Wat telling there is no container of miracle liquid to be seen. Perhaps the apsaras have this missing stash, which may account for their longevity?

Devatas meanwhile are female deities who stand guardians at doorways and generally they are surrounded by deeply etched framework as if forming a little guardsman’s hut as seen outside Europe’s Palaces.

Maybe it’s better just to enjoy these striking and exotic beings without worrying about the precise differences? In these pages I’ll use the word apsaras to refer to both apsaras and devatas, and accept any brickbats from purists.

Apsaras are not to be confused with other numerous carved images associated with Khmer mythology, or classic Indian Hindu and Buddhist texts.

The greatest number of apsaras in a single Khmer temple, and so perhaps the most easily viewed, are the nearly 1,900 that grace the walls, towers, and galleries of the jewel in the Angkor crown, Angkor Wat. Although, despite this crowd, if you want to see apsara super models, drive the ten minute or so journey from Angkor Wat, through the city of Angkor Thom and under Victory Gate to the Thommanon, a small temple which is, in my opinion, the catwalk where the super models strut their stuff.

Apsaras decorate the walls of many, although not all, Khmer temples – perhaps because of the evolution of beliefs or philosophies, or because of the era in which a temple was built, or perhaps the geographic location.

The temples of Phimai and Phnom Rung, built in northern provinces of the Khmer Empire, now Thailand, do not have near-life sized apsaras and the same is true of Beng Mealea, a large temple ruin a few kilometres from Angkor, and yet these are all considered temples of the Angkor Wat style. Apsaras are however resident in the Bapuon, Pre Rup, Ta Keo and Bakheng, and some of the finest apsaras to be seen are at Bateay Srei – and yet all these temples pre-date Angkor Wat.

No matter where you come across apsaras, there’s something about them – I’ve gazed at thousands. I’ve closely scrutinised hundreds of faces. There’s definitely something about them.

More about these dames, broads and dolls on another day.

‘If you don't follow your dreams, you might as well be a vegetable’.

I’m reading the newly published Annie Proulx book about her life and her home in Wyoming. Incomparable prose from the author of ‘Shipping News’.

And in reading this story it reminds of my brief experiences when in 2003 I drove across Wyoming.

From Yellowstone National Park in the North-Western corner to Cheyenne on the South-Eastern corner of this state, from where I barrelled out of the big sky state, like the bullet from a Colt 45, down Interstate 25 on my way to Loveland in Colorado, a gateway to the Rocky Mountains National Park.

The National Parks at the extremities of this drive are spellbinding; the journey in-between is unremarkable, in a remarkable way.

I leave Old Faithful Inn at about 7 a.m., and skirt round the northern end of Yellowstone Lake, where a Grisly Bear had been spotted the day before; a long, winding valley descended from snow clad peaks to a semi-desert landscape right out of a western movie.

It's a shock to arrive at Cody with the stupendous Yellowstone wilderness still in the rear view mirror; but a stop in the town is mandatory - as an aging warrior would you want to miss the chance to see a historical centre dedicated to the legendary Buffalo Bill? He founded the town with others, and he lived here for a time, before fame and fortune came along.

Bill was a colourful aging warrior if ever there was one; in his later years he fought for conservation, and the rights of indigenous Americans, and women; not activities you’d expect of a wild west legend.

There’s nothing like, I think, sliding behind the steering wheel with a map on your lap, rather than a GPS in your face, and heading into the personally unknown – it’s the kind of thing that I imagine many aging warriors like to do: exploring, discovering, meeting, sharing; it’s an experience exemplified in a wonderful movie titled ‘The World’s Fastest Indian’, about Burt Munro, an aging warrior from New Zealand, and his greatest love; in the movie Anthony Hopkins, as Burt, says, ‘If you don't follow your dreams, you might as well be a vegetable’.

On this trip I had already travelled from Los Angeles to Yosemite – where the young, gawky, piano-playing photographer Ansell Adams began his journey on the way to being, probably unarguably, the greatest landscape photographer of the twentieth-century.

Then I headed first north to Silver Springs, and then east to Fallon where I got my first and last American speeding ticket; then east again on the ‘loneliest road in America’, Route 50 across Nevada; at one point I stopped to look at the route taken by the riders of the pony express, a lonely track as straight as an arrow, across what I imagine to be sagebrush; impossible I would have thought to be in this lonely spot and not hear the wildest and most dangerous days of the wild west whispering on the wind. To the east, across my path, rose a range of snow-covered peaks, and some distance beyond these, Bonneville Salt Flats where Burt imagined realising his dream.

And that’s how I came to be east and south of Yellowstone meandering along Highway 20 in Wyoming about midday; I was in the thermal springs metropolis of Thermopolis for two minutes as I drove down the main street; the Mustang and I then sashayed between the steep slopes of a gorge through which a road, railway, and the racing Bighorn River squeezed.

Then along the shores of the Boysen Reservoir, and into Shoshoni I rolled, a dry and dusty township, as I recall, named after the Native American tribe; and as the afternoon light turned golden, and the rolling countryside, became a palette of shocking pinks, emerald greens, violets, and golden yellow I headed due east to Casper.

Then along the shores of the Boysen Reservoir, and into Shoshoni I rolled, a dry and dusty township, as I recall, named after the Native American tribe; and as the afternoon light turned golden, and the rolling countryside, became a palette of shocking pinks, emerald greens, violets, and golden yellow I headed due east to Casper.

I made a meal stop at a road house, there a table with a family nearby, and I don’t know what possessed me, but on my way out I sauntered over and handed the kids the accumulated, heavy American coinage in my pockets; I meant it as an act of kindness, and the coins were well received, but I still wonder eight years later what those people thought. But hey, at least I can remember the event and for an aging warrior that can’t be all bad!

And that’s what I remember of Wyoming, and why I had the opportunity, no matter how briefly, to look at a beautiful and yet stark part of the USA.

Thanks Annie for giving me the opportunity to reminisce. And reader, if you got this far, thanks for following along.

Saturday, 29 January 2011

"Faith is taking the first step even when you don't see the whole staircase"

So said Martin Luther King Jr.

For this quote, I’m indebted to Bob Beaudine, author of an extraordinary book ‘The Power of Who’; I’d not come across it before and I’m an avid quote collector! So, if you have little-known quote gems that I’m not likely to come across on-line, or in quote compendiums, please email them to me.

Anyway, thanks Bob, for the book and the quote.

The quote caught my eye because I’ve just returned from another stint in Thailand, living in the home that I’ve established; and I took the first step to living in Thailand in the same spirit; I took the first step without knowing exactly what was ahead on the staircase.

So, for the last five weeks, as I’ve been careering though traffic from hell on my motorcycle, and as I’ve been strolling along golden sands looking at the reflections of towering storm clouds in the damp sand at ocean’s edge, and as I’ve been making boon by giving offerings to Buddhist monks as they wander dawn streets and laneways, and as I’ve floated and drifted in a cove that comes from the picture book of paradise – I’ve been taking stock and considering my decision.

What are some of the things I’ve discovered in moving to another world?

- You can’t foresee every issue and occurrence – there is inevitable risk,

- Racist behaviour is only a few seconds away, by someone, in numerous, perhaps most, encounters,

- It’s unlikely that the government of the country you are leaving will make it easy,

- There’s one way, and one price, for the foreigner, and another for the local,

- The outcome of any process is completely unpredictable, except that …

- Everything will take longer that you expect, and

- You will never have all the correct documentation on the first or even second encounter with bureaucracy,

- And away from our secure and, oh so sterile world, it is not a cliché to say, life is cheap.

I suppose these could be the first in a very much larger list of experiences; despite these discoveries, I’ve loved just about every minute of my adventure, which is what my life has become, so far.

Now you may say that if I couldn't foresee these discoveries then I must be very stupid or naive, and that may be true; but there’s a difference between assuming and knowing.

And I think to know is infinitely more rewarding than to presume.

So, I’m glad I made a leap of faith. I’ve been rewarded with a million new experiences.

I’ve made some very interesting new friends, who accommodate my almost complete lack of ability to communicate, because I don’t speak their language.

I’ve seen some astonishing things; and I’ve been to some extraordinary places.

And perhaps most of all, I’ve been allowed to share in the lives of others as they make their way through life circumstances very, very different from mine, with great honesty, dignity, and a tremendous amount of good humour.

So, back to my impulsive decision to move to Thailand. After five years of discoveries would I, as an aging warrior, do it again? Yes - in a heart beat.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)