I’m not sure about other aging warriors, but I often wonder whether my later life decisions are sane and practical; is it practical, for example for me to move to Thailand?.

And then I get to thinking about life in the western world and the cultural differences with Asia and I perk up because I realise that staying put in Australia, for me, is not an option; and anyway discovering Asia has been a joy, and I’m always excited at the chance to return there.

One rewarding discovery for me has been the ancient Khmer empire; I recall during my mid to late twenties reading about Pol Pot and Cambodia and I remember never being quite clear about the complex drama that was being played out; I don’t know that I ever resolved the conundrum.

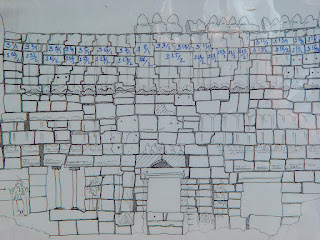

Flash forward to 2004 when I first visted Cambodia as a consequence of discovering a wonderful book, ‘Ruins of Angkor’, full of photographs taken in 1909 by Frenchman P. Dieulefils when the temples were probably little different from when Europeans first re-encountered them in mid nineteenth century; they were tumbling down, they were overgrown by grasses, shrubs and stained by mould, bat droppings, and by the accumulated filth of centuries. And yet, this in no way seemed to diminish the attraction of these extraordinary works of art – these great places of worship. In fact, their ruinous condition was their attraction.

Way back in a February post entitled Dames, Broads and Dolls, I wrote about apsara, celestial dancers, that adorn numerous khmer temples … and I’ve pondered on their similarity because no matter where you come across apsaras, there’s something about them – I’ve gazed at thousands. I’ve closely scrutinised hundreds of faces. There’s definitely something about them.

Georges Coedes, doyen of Khmer Empire academics until his death in 1969 wrote, ‘ … the figures of apsaras which adorn the walls of Angkor Wat are not there solely for the pleasure of the eye: their role is to transform this cold stone dwelling-place into a celestial palace’. So, it seems, he believed that these decorative girls – and all the other temple decorations - were more than simple representations of divine beings; rather he believed they were to evoke divine worlds and bring them to life - in the temple.

So imagine, night has fallen and beyond the outer temple enclosure in the jungle there is rustling, shrill cries, and throaty rumbling. Inside the temple, the great Khmer king Jayarvarman VII is making his way to the inner sanctum of Angkor Wat – his vast retinue of attendants follow although only he and the attending Brahman priests will climb to the highest terrace. The sound of the pacing thousands echo through the galleries and terraces.

Flares flicker and gutter as breezes find their way along colonnades and through windows and doors, golden thread woven into vividly coloured banners shimmer, fabric ripples, incense drifts – and across the rough hewn stone walls shadows tumble, chase and slide at the passing of this vast crowd.

Now the celestial dancers are not so inert – but rather they seem to seductively undulate, sway, and deeply genuflect - and the guardian devatas in deepening shadows alternately recede and emerge as flames flicker. Light gleams on vast golden Buddhas and Hindu deities. Bats zigzag and squeak. Bells and gongs ring, and other instruments tinkle. And fruit and blossom offerings scent the humid night.

The king strides the great encircling galleries with their carved reliefs - floating apsaras in heaven and tormented souls in hell – torture and mayhem – and scenes of the royal court - he pauses by an image his grand-father King Suryavarman II who commissioned this vast building, standing on his war elephant leading a vast army of Khmer and Siamese troops on its way to wage war – to kill and plunder, pillage and enslave.

If apsaras talked - and who knows maybe they do when the tourist hoards are gone - they would tell you they are accustomed to molestation and violence. They have been fondled by perhaps millions of visitors over hundreds of years, for centuries robbers have been hacking their inscrutable faces from shapely bodies to make a quick buck, and restoration works have deconstructed, chemically treated and reconstructed thousands.

The most recent apsara pogrom occurred in temples where Pol Pot’s armed thugs took refuge between 1975 and 1979 amusing themselves using life-sized apsaras for target practice. Happily, by and large, they otherwise left the temples relatively unharmed – a miracle given what the Khmer Rouge did to fellow citizens – these acts of temple vandalism were the very least of their mindless activities.

If you visit Ta Prohm at Tonli Bati, a tiny Khmer temple 20 or so kilometres from Phnom Penh, the smiling apsaras you see are in stark contrast to the depressing depressions of the killing fields of Choeung Ek a few kilometres away where about 17,000 were slaughtered after being brutally tortured by interrogators - fellow citizens - at prison S-21. At the tall glass-sided memorial there are no smiles – just the bared upper molars of more than 8,000 cavernous skulls arranged on shelves as if in some library in the bowels of hell. Oh that these poor souls could be renovated as effectively as apsaras.

Fortunately, in the early nineteen-eighties the Archaeological Survey of India – the ASI - was selected to undertake Angkor restoration works; their proposals were accepted because of their sympathy with Khmer culture and similar work done on many Indian temples.

The scale of the renovation works was staggering – entire portions of the temple were rebuilt – or at least renovated. Bat nesting was eliminated and the stone-corroding acid from their droppings was neutralised. Micro-vegetation was stripped away. Damaged stones were rejuvenated. Surfaces were chemically cleaned, and protected. And inevitably, fortunately, the apsaras received the same TLC – which is why their smiles are broader than any other Angkor apsaras. Yes, you’re right – that’s not true – but it would be nice to think it was, given the difficulty involved in the restoration.

Like the ugly duckling that became a swan - Angkor Wat was transformed; and all this was achieved as a, post Pol Pot regime, civil war raged around Angkor. India’s Ambassador to Cambodia later wrote: ‘There was no electricity, no health facilities, no communication with the outside world. In short, the working conditions were extreme. But for seven to eight months at a stretch for seven consecutive years from December 1986, the ASI experts spent all their energies in saving Angkor Wat, shoulder to shoulder with their Khmer brethren’.

The work of preserving Angkor Wat – and many other temples – continues with the expertise of many nations.

However, not all the numerous temples in the Angkor region received the same focused attention as Angkor Wat. Even today, in temples where carvings are more exposed to weather, stone contours have softened and only the faintest images remain, moss coats surfaces, tiny plants thrive between blocks, and the webs of marauding spiders form gossamer veils. And in some temples it’s clear that restoration has been, at best, less than perfect – especially when Frangipani’s upper torso has lily’s navel - because sometimes reconstructions are completed with stone blocks that are available - rather than those that are missing.

If you wander through the valleys, across the plains and over hillsides of the one-time Khmer Empire you'll get to meet many more of these apsara beauties, some as fresh and clean as if they were carved yesterday and others not. Their costumes and appearance change depending on the era in which the carvers gave birth to their creations. And there is something about them – some shared characteristic.

Apsara frequently hold flowers, or their diaphanous sarongs are discretely decorated with blossoms, and sometimes they are surrounded by elaborate carved foliage, or the background from which they protrude is a field of repetitive floral symbols.

Perhaps the most common flower represented is the sacred flower of Hindu mythology, the lotus and many apsaras hold a long stem lotus that loops behind their neck.

Every apsara is unique – some barely so - but others are like chalk and cheese. They all have as much variation in eyebrows, eyes, chins, lips and mouths, gestures, body shape, hairstyle, and apparel and accessories as you’d see as any crowded mall anywhere in the world.

I am told several hold books – and that only two, among all the smiles, display teeth - I can vouch that there is one. But I won’t tell you where she is – go look for yourself.

But what is it about them? There is a consistent feature. It’s on the tip of my tongue.

In my first post about apsaras I began by writing that many Asian women have extraordinarily exotic features – added to which they frequently wear clothing that tantalises – like the Chinese cheongsam and the Vietnamese ao dais, for example.

If you hang around you’ll be able to revisit the Khmer Empire, apsaras and the similarity they universally share, and beautiful women in another post some time soon.

Thanks for spending these few minutes with me.

Saturday, 25 June 2011

Saturday, 18 June 2011

Maturity is no antidote against stupidity!

So this morning as I clamber from my bed I know with a certainty that I consumed too much alcohol last night. Way too much. Stupid. Absurd.

So in my fragile state I’m tapping away at this post because I’ve missed blogging in recent months, and because my own stupidity reminds me that I have thoughts I’d like to share about this very subject.

Stupidity. I’m not sure about your world, but mine really is full of breathtaking stupidity.

More and more I see ordinary citizens of the world in which I live being treated like helpless children despite their obvious maturity; or like criminals instead of hapless innocents trapped in a mire of revenue-raising regulations; or heroes when they should be perceived as villains; or wealthy when in fact they are just making ends meet as taxes and the cost of living soar; or intellectuals when they are nothing more than pompous and misguided blowhards. I won’t go on, at 68 time is too short.

In previous posts I’ve identified my ‘PC21’ - my personal conflicts with the twenty-first century - and this list perfectly illustrates some of the conflicts that often cause me to feel disenfranchised, as stupidity gets a tighter and tighter grasp on society, and as it slowly strangles my own ability to live my very modest and unobtrusive lifestyle.

Since I last posted I’ve spent some time in my Thai home; living in a third world country is a welcome reprieve from western society.

But I've also spent some time in corporate Australia and there’s certainly no escape from stupidity there. Less people doing more and more work, multitasking our way to mediocrity while all the time loudly proclaiming corporate values of quality and thought leadership; eliminating competent employees and then immediately replacing them with more educated but less competent and capable people - qualifications are rarely a substitute for experience; demands for increased productivity and quality while acting in ways that reduce worker engagement; shunting people around organisational structures that on paper work perfectly, but in the real world defy implementation; English-mangling jargon that makes the simple incomprehensible; it’s a place where talking in meetings eliminates any possibility to doing; and, in my own area of specialisation, we’re trying to turn selling into a science rather than mastering the art.

This is unquestioningly the age of absurdity. But there’s not much point whining - better to fight back. But what to do? What weapons do I have against this global tsunami of absurdity? Or do I have a shield large enough to protect me?

Well, I’ve already posted the steps that I’ve taken to try and counter my personal conflicts with this century.

And recently I’ve been trying to make sense of this age, and trying to discover whether others have similar frustrations to my own, so I’ve been reading ‘The age of absurdity’; for me it’s riveting and if you find yourself wondering what has happened to life as you once knew it, then this is a book for you.

It’s one of the few paperbacks I have, given the transient nature of my lifestyle, and its pages are scored with underlined paragraphs and graffiti, pages are dogeared, it falls open at many places where the spine has been creased, and it has post-it notes and scraps of paper poking out between every other page.

If you sense that you are in conflict with the twenty-first century I highly recommend you read ‘The age of absurdity’ and react, and resist some of the nonsense that threatens to overwhelm us.

Reading it has certainly helped me see the absurdity - the stupidity - that pervades our society and it’s given me great new insights that help me stiffen my resolve to resist.

How to resist? What to do? It’s tough because the absurdity of this age is omnipresent. But on a practical level here’s my discipline:

By applying these disciplines I don’t eliminate absurdity, but I do cause my focus to be on what I am doing, rather than what everyone else is doing; and that works for me.

As is self evident, Buddha accompanies me on this journey of reflection and in an early post I wrote that it was ‘my growing conviction is that there could be no better guide, no better plan, for responding to pc21, than the way for living life as proposed by the Buddha’; his eightfold path is a very accessible tool for living.

Author Michael Foley writes in the ‘The age of absurdity’ opening chapter, that ‘Buddha’s metaphor for the liberated mind was a sword drawn from its scabbard’ - so perhaps Buddha’s image and my self-professed role as an aging warrior are entirely appropriate for trying to liberate myself from this age of absurdity?

And perhaps maturity can be an antidote to absurdity - and stupidity?

http://www.amazon.com/Age-Absurdity-Modern-Makes-Happy/dp/1847396275/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1308383280&sr=1-1

So in my fragile state I’m tapping away at this post because I’ve missed blogging in recent months, and because my own stupidity reminds me that I have thoughts I’d like to share about this very subject.

Stupidity. I’m not sure about your world, but mine really is full of breathtaking stupidity.

More and more I see ordinary citizens of the world in which I live being treated like helpless children despite their obvious maturity; or like criminals instead of hapless innocents trapped in a mire of revenue-raising regulations; or heroes when they should be perceived as villains; or wealthy when in fact they are just making ends meet as taxes and the cost of living soar; or intellectuals when they are nothing more than pompous and misguided blowhards. I won’t go on, at 68 time is too short.

In previous posts I’ve identified my ‘PC21’ - my personal conflicts with the twenty-first century - and this list perfectly illustrates some of the conflicts that often cause me to feel disenfranchised, as stupidity gets a tighter and tighter grasp on society, and as it slowly strangles my own ability to live my very modest and unobtrusive lifestyle.

Since I last posted I’ve spent some time in my Thai home; living in a third world country is a welcome reprieve from western society.

But I've also spent some time in corporate Australia and there’s certainly no escape from stupidity there. Less people doing more and more work, multitasking our way to mediocrity while all the time loudly proclaiming corporate values of quality and thought leadership; eliminating competent employees and then immediately replacing them with more educated but less competent and capable people - qualifications are rarely a substitute for experience; demands for increased productivity and quality while acting in ways that reduce worker engagement; shunting people around organisational structures that on paper work perfectly, but in the real world defy implementation; English-mangling jargon that makes the simple incomprehensible; it’s a place where talking in meetings eliminates any possibility to doing; and, in my own area of specialisation, we’re trying to turn selling into a science rather than mastering the art.

This is unquestioningly the age of absurdity. But there’s not much point whining - better to fight back. But what to do? What weapons do I have against this global tsunami of absurdity? Or do I have a shield large enough to protect me?

Well, I’ve already posted the steps that I’ve taken to try and counter my personal conflicts with this century.

And recently I’ve been trying to make sense of this age, and trying to discover whether others have similar frustrations to my own, so I’ve been reading ‘The age of absurdity’; for me it’s riveting and if you find yourself wondering what has happened to life as you once knew it, then this is a book for you.

It’s one of the few paperbacks I have, given the transient nature of my lifestyle, and its pages are scored with underlined paragraphs and graffiti, pages are dogeared, it falls open at many places where the spine has been creased, and it has post-it notes and scraps of paper poking out between every other page.

If you sense that you are in conflict with the twenty-first century I highly recommend you read ‘The age of absurdity’ and react, and resist some of the nonsense that threatens to overwhelm us.

Reading it has certainly helped me see the absurdity - the stupidity - that pervades our society and it’s given me great new insights that help me stiffen my resolve to resist.

How to resist? What to do? It’s tough because the absurdity of this age is omnipresent. But on a practical level here’s my discipline:

- I try to simplify my thinking - and eliminate or reduce the mental muddle that often accompanies anything we do in this age, and

- I try to focus on doing everything with complete attention rather than multitasking myself into mediocrity, and

- I try to eliminate or avoid sources of information, like newspapers, that cause me to confront the absurdity, and

- I try to avoid accumulating.

By applying these disciplines I don’t eliminate absurdity, but I do cause my focus to be on what I am doing, rather than what everyone else is doing; and that works for me.

As is self evident, Buddha accompanies me on this journey of reflection and in an early post I wrote that it was ‘my growing conviction is that there could be no better guide, no better plan, for responding to pc21, than the way for living life as proposed by the Buddha’; his eightfold path is a very accessible tool for living.

Author Michael Foley writes in the ‘The age of absurdity’ opening chapter, that ‘Buddha’s metaphor for the liberated mind was a sword drawn from its scabbard’ - so perhaps Buddha’s image and my self-professed role as an aging warrior are entirely appropriate for trying to liberate myself from this age of absurdity?

And perhaps maturity can be an antidote to absurdity - and stupidity?

http://www.amazon.com/Age-Absurdity-Modern-Makes-Happy/dp/1847396275/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1308383280&sr=1-1

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)